Overview

Teaching: 60 min Exercises: 6 minQuestions

Why is Unix (Linux) a standard platform for neuroimaging?

Objectives

Understand some tenents of Unix philosophy and how these support reproducible research

Review streams and pipes

Describe little languages (globbing, regexps, sed, awk, grep) and how they can be used for basic tasks

Intro to make

Why is Unix (Linux) a standard platform for neuroimaging?

If you do neuroimaging, chances are that you have been exposed to Linux, the open source version of Unix, which was first developed by AT&T in the late 1960’s. (Or it might be more accurate to say that Linux has been exposed to you.) There are in fact many distributions of Linux that you may have heard of or use, including Debian, Ubuntu, CentOS and RedHat. If you use Amazon Web Services you may use Amazon Linux, which is most closely related to CentOS. If you use a Macintosh you are running OS X, an operating system which grew out of an early version of Unix.

For the purposes of this tutorial, all Linux or Unix operating systems are similar in that they allow you to issue certain commands in a shell (here we assume bash, a Bourne-again version of the original Bourne shell called sh). The shell is in fact a programming languages in its own right, allowing you to write scripts with looping and conditional constructs and to save them to reexecute the command sequences. In a shell script you can incorporate not only programs that are part of the Unix environment, but programs that are part of neuroimaging packages (e.g. FSL, FreeSurfer, Advanced Normalization Tools) or programs that you have written yourself (e.g. in Python or R, or any scripting language).

So how does an operating system that is over fifty years old at its roots become the most commonly used platform for wild and wacky youthful neuroimaging? The power of the Unix programming environment comes from its design philosophy, which is well articulated by Mike Gancarz’s book “The Unix Philosophy.” This philosophy really describes a methodology, which is still incredibly relevant to neuroimaging science today. Some of the tenents of this philosophy are as follows:

- Small is beautiful (Make each program do one thing well)

- Every program is a filter

- Prototype quickly

- Make portability a priority

Let’s deconstruct these one by one. First, Small is beautiful. It is much easier to write and maintain a small program than a large one. The more features you add, the more likely it is to malfunction somewhere and the harder it will be to support. This is why Unix programs tend to do small and weird little things that make absolutely no sense at first. For example, why is there a program just to echo its arguments to the screen? By themselves they are not overly useful but in the context of other programs that do other things, they are very useful. Small and beautiful programs can be used in multiple places in scripts to do their one trick well.

This philosophy is clearly relevant to neuroimaging and to science more generally. Scientific workflows change frequently and programs that do a single thing are more likely to last and to be used than programs that “bundle” features together.

Second, every program is a filter. This means that programs accept data (normally text) as input and generate text output. They don’t sit around being interactive with the user, asking for inputs or prompting for outputs. This allows us to use pipes and redirection to link together Unix utilities in many creative ways. This works very well for text data, but is less clear for neuroimaging files, where standard binary formats such as NIFTI make it difficult to write simple filters for neuroimaging data. Many programs require multiple files of different formats as inputs. However, remembering the real purpose of a program (to filter data) helps us to recall why we shouldn’t include lots of interactive features when they are not necessary.

Unix is built on the concept of creating a prototype of your program quickly. In neuroimaging this is particularly important - most programs don’t get beyond the level of first prototype because the research doesn’t pan out, better methods emerge, or they are very limited in scope. It’s better to just do it than to spend a lot of time planning or creating application specifications. So this makes a lot of sense.

Finally, portability is more important than efficiency. It’s much better to write a small script using a little language (we’ll talk about those) that is relatively slow than to write an optimized C program to do the same thing that is faster, but only runs on some specialized hardware. In general, because computers continue to get faster, ease of programming and ease of sharing trump execution time. Scripts themselves are quite portable and people can read what is inside of them and steal parts for own use.

Linux is also free, a factor that is incredibly important in science. Money for research is incredibly scarce, and less money for licenses and software packages means more money for people and for the work itself. It is open source, which means that source code is publicly available and can be modified and redistributed. This support for transparency and collaboration is also a critical factor in the popularity of Linux as a platform for science.

Little languages are a key element in Unix power use

It is easier to implement a task-specific language than a general purpose one. Thus, Unix is filled with “little languages” that allow users to carry out certain tasks. Some of these languages are very relevant to neuroimaging tasks today, and we will introduce these in the context of normal, work-a-day neuroimgaging life. We will also review standard streams, pipes, and file redirection because they are so critical to linking together Unix commands with little languages.

The following is an outline of what we will cover:

- Wildcards

- Standard streams and pipes

- Regular expressions and pattern matching

- Text editing (

sed) - Record manipulation (

awk) - Finding things (

find) - Workflow (

make)

This workshop is an hour. This isn’t long enough to learn even one of these topics well. The purpose of this workshop is only to convince you that you can use these tools in combination to do some tasks that are common in neuroimaging.

If you are interested in workflow specifically, there will be a breakout session on Thursday where we will discuss make in more detail.

> ## Download some example neuroimaging data

To follow along with this tutorial you need to get some data. We have downloaded the “BNU1” data set from Beijing Normal University, (He,Lin) from the Consortium for Reliability and Reproducibility (CoRR) [link here] (http://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/CoRR/html/bnu_1.html). If you do not already have access to this data from NITRC or COINS you will need to register and request access. To streamline this process we have copied the data to the computer used for this workshop,

it.ibic.washington.edu. The data are located in/neurohackweek/bnu1.

If you are doing this workshop live at neurohackweek 2016, create a directory called

bnuin your home directory (or whatever you want, really) and copy the data to that directory:

mkdir bnu cp x ~bnu

If you are following along with this lesson yourself, download the data from the web site above and put it into

~/bnu.

Wildcards

Wildcards, like the joker, are characters that match other characters (you may also hear this called “globbing”). Wildcards are useful because the slowest aspect of interacting with the command line is typing. The fewer characters you need to type, the faster you can work. It’s that simple. So you can use wildcards to “stand in” for other characters when you refer to files in the file system.

| * | zero or more characters, but not starting with a . |

|---|---|

| ? | exactly one character |

| [ab] | a or b |

| [a-c] | a, b or c |

Probably the most important thing to remember about wildcards is that they are not the same as regular expressions - the syntax, as we will see, has some similarities but also some differences that can make learning regular expressions confusing if you have mastered globbing.

Unpacking neuroimaging data

Let’s use wildcards now to unpack the neuroimaging data you previously downloaded. We can match all the

.tarfiles with the wildcard*.tar.

for i in *.tar do tar xvf $i done

Standard streams and pipes

A very important concept in Unix is abstraction of input/output (I/O). This abstraction supports the writing of programs as filters. Conforming Unix programs can read from and write to three special streams: standard input (stdin), standard output (stdout), and standard error (stderr). These are referenced by specific file descriptors (0, 1, and 2) used in the underlying C code to read and write from these streams. Thus, these can be “wired” to specific files in the file system, the terminal, or other output devices.

Let us explore this with the program cat as an example. By default cat reads its standard input and writes to standard output. By default these are wired to the terminal. So if you type the following, you will see your input hi and there echoed to the terminal. Note that CTRL-D (represented as ^D) marks the end of the input file (or EOF).

cat

hi

there

^D

You can redirect the stdout of cat into a file instead of having it echoed to the terminal, with a redirection character >. So if you type:

cat > output.txt

hi

there

^D

you will now have a file called output.txt.

cat can accept file names as arguments to use as stdin instead of the terminal. So you can check what has been written to output.txt by the following:

cat output.txt

The contents of this file are written to stdout, wired to the terminal. The same thing can be accomplished by redirecting standard input from the file using the redirection character <:

cat < output.txt

You can copy the contents of this file by redirecting stdout as we did before.

cat output.txt > output2.txt

Pipes allow us to connect standard output of one program to the standard input of another program. Let us use the program wc which counts the number of characters, words and lines in a file. Like cat, we can call it simply by specifying that the stdin should come from a specific file.

wc output.txt

However, we can use a pipe to wire the output of a sequence of commands to the stdin of wc:

cat output.txt | wc

While catting a file as input to another command is overkill here, we will see that with more complicated pipes, it is often unnecessary to create temporary files.

We have spoken about stdin and stdout but not stderr. stderr is a channel for error messages. Let’s see this in use. If you try to cat a filename that does not exist, you will get an error. Try redirecting the output of this command to a file.

cat nonexistentfile.txt > error-message

Note that stderr is wired to the terminal and stdout is directed to a file. To get the error message into a file, you need to specifically direct stderr, or file descriptor 2, to a file.

cat nonexistentfile.txt 2> error-message

Although all “traditional” Unix programs use these conventions, many neuroimaging programs do not accept stdin from a pipe and do not separate stderr and stdout streams. When redirecting output to a log file you should not make any assumptions!

So back to work on neuroimaging.

One of the first things that you normally do after downloading an open data set is to take an inventory of what you have (and make sure it corresponds to the published description) and organize the data for processing. First, let’s combine file globbing and pipes to count how many subjects we have in two ways.

echo 00* | wc -w ls -1d 00* | wc -l

In the example above, we used the prefix

00to specify that we are interested in only the subject directorys (which all start with those numbers) and not any other stuff that we may have in there (e.g., the original tar files or any scripts we might write). We can useechoand file globbing to get the list of subjects, or we can uselsto list them as a single column.

As we all know, in longitudinal studies some people don’t come back. Let’s count how many anatomical images we have at each time point:

ls -1 */session_1/*/anat.nii.gz| wc -l ls -1 */session_2/*/anat.nii.gz| wc -l

As you can see, there are indeed more anatomical scans in the first session than in the second. We’ll have to do a more complex inventory of data.

Regular expressions

Regular expressions (or regexps) are sequences of characters that describe a pattern to match to other strings of characters. They are implemented in many “little languages” as a way to describe search strings to be used in many contexts. One confusion is that there are two major flavors of regexps: basic and extended. Different Unix utilities will use one set or the other - so if you are baffled at why a tried and true expression is failing, check to see that it is supported. Here is a good [reference] (http://cavepopo.hd.free.fr/wordpress/bash/about-regular-expressions-basic-extended-2) for basic versus extended regular expressions and more detail than we will cover here. Another confusion is that filename wildcards (globbing) are not regular expressions, although on the surface they are a bit similar. Specifically, the conventions for wildcards and regular expressions are different, and regular expressions are much richer. In wildcards, a * matches zero or more characters. In regular expressions, as shown in the table below, a * indicates zero or more repetitions of the character that preceeds it.

Below is a simplified summary of commonly used regular expressions. (See a reference manual for complete details.)

| Operator | Match |

|---|---|

| . | Matches any single character. |

| ? | The preceeding item is optional and will be matched at most once. |

| * | The preceeding item will be matched zero or more times. |

| + | The preceeding item will be matched one or more times. |

| {N} | The preceeding item is matched exactly N times. |

| {N,} | The preceeding item is matched N or more times. |

| - | Represents the range |

| ^ | Matches the beginning of a line. |

| $ | Matches the end of the line. |

Sed

sed stands for “stream editor” although I remember learning that it was named after some of its more common functions: substitute, extract and delete. The purpose of sed is to process strings (from stdin or a file), operating on each line. Digital Ocean has a nice [tutorial on sed] (https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/the-basics-of-using-the-sed-stream-editor-to-manipulate-text-in-linux) that is far more comprehensive than what we’ll do here. For now, we’ll just discuss one of the most popular uses of sed, which is string substitution.

The general format of sed substitution is as follows:

~~~

sed ‘s/pattern/replacement/g’

~~~

The text in single quotes is the command for sed. The first character, s is the substitution command for sed. pattern is a regular expression that is replaced by replacement. The final character, g, means that all occurrances of the pattern should be globally replaced (not just the first).

Back to work…

We need to find out who has anatomical data from time 1 and not time 2 (and also if there are any new people at time 2 who weren’t scanned at time 1).

ls -1 */*2/*/anat.nii.gz|sed 's/\/.*$//g' > time2 ls -1 */*1/*/anat.nii.gz|sed 's/\/.*$//g' | grep -v -f time2In the first command, we use file globbing to list the names of all anatomical scans in the second session. It is helpful to try the

lspart of the command without the pipe to see more clearly what it does. We want to strip away everything but the subject ids to create a list of subjects who have anatomical scans in time 2. To do this, we use thesedsubstitute command, specifying that we should replace everything beginning with a forward slash (/) until the end of the line with nothing (note that there is nothing specified where the replacement would normally be). The standard output fromsedis redirected to a file (time2)In the second command, we repeat the same pattern to identify subject ids for time 1. This standard output is used as input to

grep. We specify that we would like to print out all lines that do not match (-vflag) strings in the filetime2(-fflag). In this way we can see all the subjects who have anatomical scans in time 1 but not time 2.Are there any new subjects in time 2 who were not present in time 1?

Awk

Awk is a tool for processing tabular data that is named after the initials of its authors (Aho, Weinberger, and Kernighan). It is popular enough that it has been rewritten and improved, as nawk (new awk) and gawk (GNU awk). Although these variants have differences, and some scripts may work only with particular versions of gawk (for example), the general principles are the same.

A full description of awk is well beyond the scope of this tutorial. Grymoire has [a nice tutorial] (http://www.grymoire.com/Unix/Awk.html), and you can also read the comprehensive [gawk manual] (https://www.gnu.org/software/gawk/manual/gawk.html).

The basic structure of an awk script is as follows:

BEGIN { action }

pattern { action }

END { action }

Basically, awk reads a text file that is structured by fields and records, and fires code (in curly braces) when records match specific patterns. This is made more powerful by the ability to do stuff before you start reading in the BEGIN action block, and the ability to stuff at the END action block.

A common use for awk is to parse comma separated value files (csv files). In a csv file, records are lines (and the record separator is a newline character) and fields are items separated by commas within a line.

Using awk to tabulate some of our data

We can use

awkinstead ofsedto obtain lists of subjects from our globbed file lists. We would specify that the field separator should be/using the-Fflag toawk.ls -1 */*_2/*/anat.nii.gz| awk -F/ '{print $1}' > time2Here we have no pattern, only an action for every line, which is to print out the first field (

$1). This is the subject id. This may be an easier way to think about extracting fields from data than thesedapproach, which does not break things into fields.Until now we have been looking only at anatomical data, but there are other scan types as well. We can use find to see what they are, use

awkto extract the file names, and tabulate them using Unix utilitiessortanduniq.find */*1 -name \*.nii.gz | awk -F/ '{print $4}' | sort | uniq -cWhat does this tally look like for the second session?

More complex awk examples

Sometimes you just want to knock out a one liner to create a table to get an overview of what data you have. I’m wondering what’s missing in the second session. So let’s do it:

find */*2 -name \*.nii.gz | awk -F/ '{subjects[$1] = subjects[$1] " " $4} END {for (var in subjects) print var,subjects[var]}'This command builds up an associative array called

subjectsthat includes, for each subject, a list of the different scan types that that subject has. These are then printed in the END block.Note that this isn’t really a file ready for uploading to a spreadsheet - for that it would be more elegant to have a column for each scan type with a 1 or a 0 to indicate whether the scan was present.

We can do that by matching the differents scan types and keeping an array for each.

find 00*/*2 -name \*.nii.gz|sort| awk -F/ ' {subjects[$1] = $1} /dti/ {d[$1] =1} /anat/ {a[$1] = 1} /rest/ {r[$1]=1} END {for (var in subjects) print var "," d[var] "," r[var] "," a[var]}'Here every subject id is stored in the subjects array. The subject id is used to index three additional arrays (d, a, and r) for dwi, anatomical, and resting state data, respectively. In the END block, we print out the subject and the value for each subject (1 if the data exist, and nothing if it doesn’t), separated by commas.

Run this, sort the output by subject ID, and save the output into a file called

inventory.txt.

Grep

Grep, a program named for the command in ed to globally search a regular expression and print (g/re/p), searches for lines in a file (or stdin) that match something. By default grep uses basic regular expressions, but grep -E or egrep use extended regular expressions. That’s not important now but knowing it will prevent headache one day later.

Compare our data with the demographic file

In neuroimaging nothing is as much fun as merging data files. We can see how many people there are in our demographic data at each time point. We use

tailto omit the first line of the csv file because it is just header information.tail -n +2 demographics.csv | grep time1 | wc -l tail -n +2 demographics.csv | grep time2 | wc -lI normally build up extensive piped commands by looking at the output of each stage to note any surprises. Here, notice that the leading zeros of the subject identifiers are knocked off (perhaps by design, perhaps by accident, but it keeps one alert).

Let’s fix that. ~~~ mv demographics.csv demographics.orig.csv head -1 demographics.orig.csv > demographics.csv tail -n +2 demographics.orig.csv | sed ‘s/^/00/g’ » demographics.csv ~~~

Now we can merge the inventory file with important demographics using the utility

join. For simplicity we will just create comma separated input and output. We can use the-tflag to specify that the field separator for both the input and output is a comma.grep time1 demographics.new.csv | awk -F, '{print $1 "," $3}'| join -t, -j 1 - inventory.txtMake for neuroimaging workflow

Make is a build automation tool that is an essential part of Unix. When writing a program using a compiled language such as C, you typically put different functions in different files, to make it easier for multiple people to work together and to organize the project. Definitions common to several functions are stored separately and included by the files that need to reference them, to avoid replication of information. Each function is compiled into an object file, and these object files are linked together with system libraries into a single executable.

This means that if a source file changes, one or more object files will need to be reconstructed, as will the entire executable.

What this tool does is allow one to (a) express a dependency graph so that we can parallelize execution and (b) manage reconstruction of files when files they depend upon change. This is a 40 year old workflow system that does one thing well.

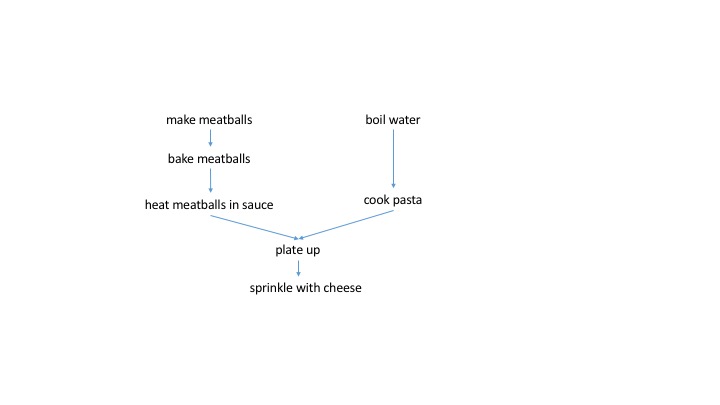

Because not everyone has experience building executables, let us take the example of making a simple spaghetti and meatball dinner. The coarse steps, written in a sort of shell script, might look like this:

- make meatballs

- bake meatballs

- heat meatballs in a jar of sauce (to meld flavors)

- boil water for pasta

- cook spaghetti

- plate up

- grate parmesan cheese on top for a gourmet touch

While this is an accurate script of the steps involved in making pasta, it is not an accurate description of how to do these steps most efficiently, nor does it describe what needs to be redone if one step fails. The key to these concepts - parallelization and fault tolerance - lies in describing a dependency graph.

A dependency graph for making spaghetti and meatballs might look like this.

Now we can see clearly that (as we intuitively know) boiling the water and cooking the pasta can occur in parallel to the whole meatball making procedure. Both the spaghetti and meatballs need to be ready to plate up. Furthermore, we know that if we burn the meatballs, we need to start over at the stage of making them. If we cook the spaghetti to a mush, we need to boil a new pot of water. However, a script does not easily convey this dependency information.

Why would one use Make to describe this dependency graph and not some cooler and newer tool? We like using Make because the recipes can be in bash. This means that the same commands we type in the terminal or use in a script can be put into a recipe. We don’t need to write any additional wrappers, or additional code, which means we get results faster and can switch things up faster. Finally, make has been around for forty years and is stable, standard on all Unix systems, and reliable. So when we hang out on the bleeding edge of neuroimaging technology, we can be certain that our workflow system doesn’t have bugs.

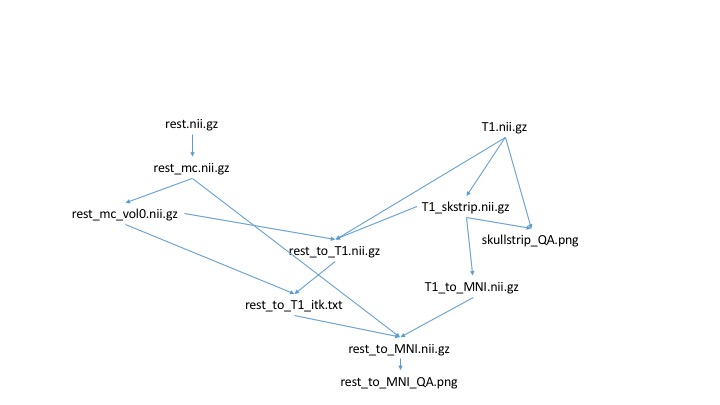

A neuroimaging workflow example

An example neuroimaging workflow pipeline can involve many steps and many different packages. Let us consider a small example of how we typically do fMRI registration. Because not everyone might be familiar with the syntax of all the tools, I will just describe these steps generally.

- Use a Python script to motion correct fMRI data

- Extract first volume of motion corrected fMRI data

- Use bet to skull strip T1 data

- Create QA image for skull stripping

- Use FSL epi_reg to register fMRI to T1 data

- Use Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) to register T1 data to MNI space

- Convert FSL registration matrix to ITK format

- Apply transforms to register functional data to MNI space

- Create QA image for registration

We can draw the dependency graph for this more relevant example:

Makefile syntax

Rules for Make are described in a text file that is traditionally named Makefile (more generally, let’s call this a makefile). The format of a makefile is a set of specifications for how to create target files from dependency files as follows:

target: dependency1 dependency2 ... dependencyN

[TAB] shell recipe to create target from dependencies

The target and dependencies are normally files, but it is possible to have dummy targets (PHONY targets) that are descriptive names rather than actual files. Note that each line of the recipe, normally written in bash, must begin with a TAB character. This is weird but a strange historical accident. As described in “The Art of Unix Programming”, the author of Make, Stuart Feldman, decided that this was a good opportunity to play with then brand-new programs to generate compilers (lex and yacc). After having troubles with lex, he just went with the pattern newline-TAB, and it worked. The program was so useful that he sent it to his friends, and a few weeks later, he had a user popluation of about a dozen people. At that point, he decided it was too late to change it.

There will be a breakout session Thursday for people who are interested in learning more about actually running Make for neuroimaging workflow, and we can do real exercises then.

Key Points

There are good reasons that Unix has been in use for fifty years